10 things I learned about ancient China from studying Chinese characters

Chinese characters have been around for thousands of years, and many of them have created traces that we can follow to discover some interesting fragments of Chinese history.

While I was working on creating the Chinese character etymology lexicon that I incorporated into Dong Chinese, I researched the origins of hundreds of the most common Chinese characters. During that process I stumbled upon these interesting tidbits of information about ancient Chinese culture. Here are ten fascinating things that I learned.

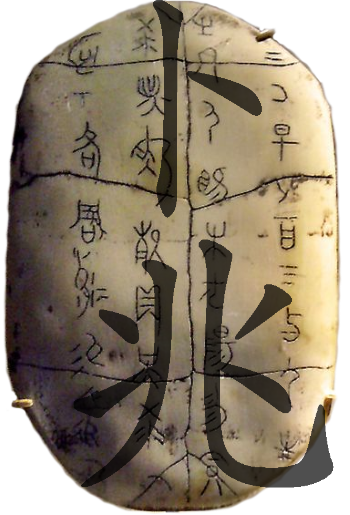

1. 兆 - Fortune-telling on bones

In ancient China, fortune-tellers would throw turtle shells and animal bones into a fire, perform divination from the resulting cracks, and carve writings into these bones with details about their predictions. The artifacts from these writings have the oldest known form of Chinese characters, called oracle bone script, which was used in the Shang dynasty starting around 1250 BC.

Several Chinese characters allude to this method of fortune-telling:

- 兆 means “omen”, and it is a pictograph of cracks on a turtle shell, similar to those in the picture above.

- 卜 means “to divine”, and it is also a pictograph of a crack on a shell.

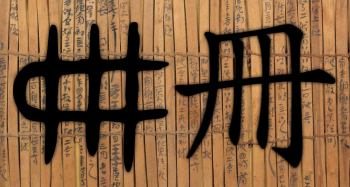

2. 冊 - Writing on bamboo strips

We know that most of the day-to-day writing in ancient China was not carved on bones, but written with ink on vertical slats of bamboo tied together with string. Unlike the remains of oracle bone script that still exists today, bamboo writings that were contemporaneous with oracle bones were not durable enough to survive over the last few thousands of years.

So how do we know that the ancient Chinese wrote on bamboo strips during that time? There are two pieces of evidence:

-

The character 冊 (simplified 册) means “book” and is a pictograph of bamboo slats bound together.

-

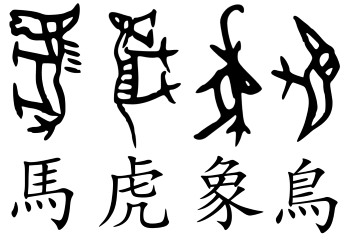

Some characters representing things that have a longer length than height, such as 馬 (simplified 马; horse), 虎 (tiger), 象 (elephant), and 鳥 (bird), were rotated 90 degrees in order to make them more convenient to write on vertical strips of bamboo. This orientation constraint did not exist on bones, but habits formed from writing on bamboo persisted when writing on bones.

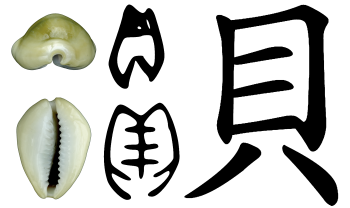

3. 貝 - Shell money

In ancient China, cowry shells were used as a form of currency.

The character 貝 (simplified 贝) represents this shell, which is why so many characters relating to money contain 貝 as a component, such as:

- 貴 (simplified 贵) - expensive

- 買 (simplified 买) - buy

- 賣 (simplified 卖) - sell

- 費 (simplified 费) - expense; fee

- 資 (simplified 资) - capital; property

- 貨 (simplified 货) - products; merchandise

- 購 (simplified 购) - purchase

- 賺 (simplified 赚) - earn; profit

- 財 (simplified 财) - riches; wealth

- 貢 (simplified 贡) - offer; contribute

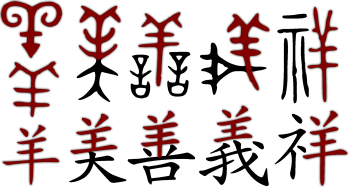

4. 羊 - Lucky sheep

In ancient China, sheep (羊) were associated with goodness and fortune, and because of this, 羊 is used as a component in characters like 美 (beautiful), 善 (benevolent), 義 (justice), and 祥 (auspicious).

- 羊 (sheep) is a pictograph of the horns on a sheep head.

- 美 (beautiful) depicts a person (大) with ornamental headwear resembling sheep horns.

- 善 (benevolent) has a sheep surrounded by two 言 (speech) components, which represent the sound.

- 義 (justice; simplified 义) is a sheep over 我 (I; me). 我 is used here as a sound component, since 義 and 我 sounded similar in ancient Chinese.

- 祥 (auspicious) is a sheep accompanied by the 礻/ 示 (spirit) component.

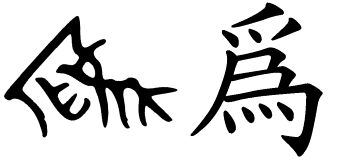

5. 為 - Tamed elephants

The character 為 (variant 爲, simplified 为) originally meant “work” or “do”, and depicted a hand guiding an elephant. It is speculated that the ancient Chinese tamed elephants to do work or participate in battle.

6. 央 - Forced starvation

The character 央 means “beg” or “plead”. It depicts a person in a cangue - a square board locked around a person’s neck, used to publicly humiliate criminals.

The cangue restricted people from reaching their own mouth with their hands, preventing them from being able to feed themselves. They had no option but to beg others to feed them, and it was common for these convicts to die of starvation as a result.

7. 黑 - Permanent face tattoos

The character 黑 means “black”, and it depicts another practice to publicly humiliate criminals - forcibly tattooing their face with permanent black ink. This punishment was referred to as 墨, and it was the least severe among the the Five Punishments in ancient China, followed by cutting off the nose, amputating a limb, castration, and the death penalty.

8. 取 - Yanking out enemies’ ears

The character 取 means “take”, and it is a pictograph of an ear (耳) being pulled off by a hand (又). In ancient China, the ears of opponents in battle were cut off and collected as tokens of victory.

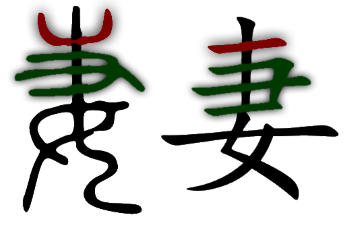

9. 每 - Marriage and hairpins

Young girls in ancient China wore braids until they turned 15, at which point they went through a coming-of-age ceremony called 筓禮 (hairpin initiation). In this ritual, the young women put their hair up in a bun and secured it with a hairpin. Wearing a hairpin signaled that the young woman had reached marriagable age.

The character 每 originally meant “young woman” and depicted a hairpin affixed the head of a woman (母). The character 每 was later re-purposed to represent a similar-sounding word, and now has the unrelated meaning “each” or “every”.

The character 妻 (wife) also depicts a woman (女) wearing a hairpin, which is being grabbed by a hand. When a woman became engaged, she would give her future husband her hairpin as a pledge.

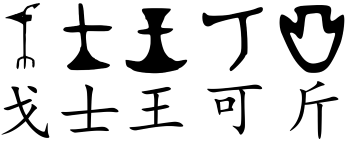

10. Axes, axes, and more axes

The ancient Chinese seemed to have an obsession with axes, drawing them from all sides and angles.

- 戈 means “dagger-axe”.

- 士 means “soldier” or “scholar”, and depicts an axe used by a military officer.

- 王 means “king”, and depicts an axe symbolizing the king’s military authority.

- 可 means “allow” or “able” and is pronounced “kě”. This meaning is unrelated to axes, but originally the character meant “axe handle”, which is now written as 柯 and pronounced “kē”. The mouth (口) component was added since 可 is only “mouthed”, i.e. used for its phonetic value.

- 斤 means “axe”, now also used as a unit of weight.

And that’s not all

All of the following characters were originally pictographs of axes (although the meaning of most of them has changed over the years), and they’re all pronounced differently:

戊戉戍戌戎

Make sure you don’t confuse them. Good luck! :)

Fortunately, most of them are not in common daily use anymore.

References

The sources for the information on this page are the Multi-function Chinese Character Database provided by the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and the historical character image database created by Richard Sears.

Want to learn how to read and write Chinese? Sign up at Dong Chinese.