Origins of the 1000 most common Chinese characters

I started working on this project about 3 years ago, writing explanations of the origins of the most commonly used Characters in Chinese. This is one of the most ambitious projects that I have ever started, and I’m proud to say that I recently reached my goal of creating explanations for the following:

- 1000 most frequent characters in books (simplified and traditional)

- 1000 most frequent characters in movie subtitles (simplified and traditional)

- all of the components contained in the above characters

- ~3000 phonosemantic compounds formed from components in the above bullets.

You can browse all of this information on the Dong Chinese dictionary.

I’ve also made this data available in an open-source GitHub repository. You can download it, raise issues, and suggest improvements on my Chinese lexicon project there.

Features

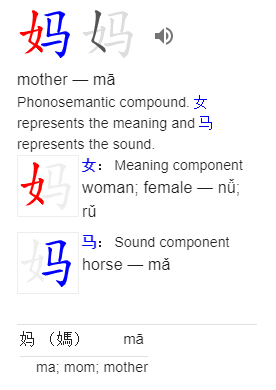

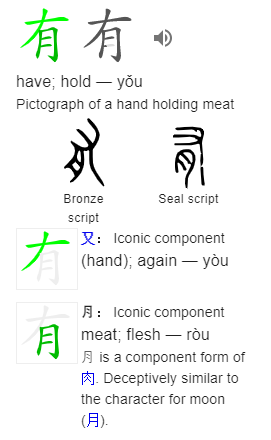

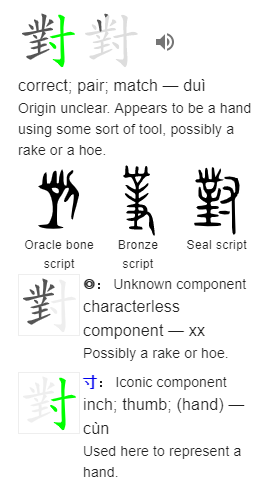

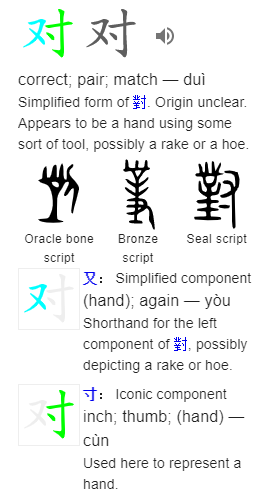

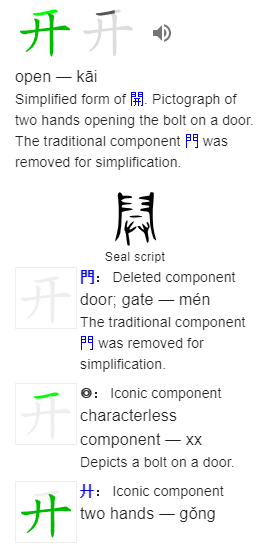

Dong Chinese shows an explanation of how characters are formed and breaks down their individual components.

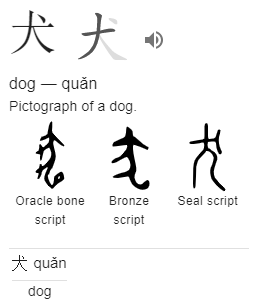

When relevant, it shows historical forms of characters to reveal their evolution.

Types of components

I’ve organized the components of characters into the following categories:

- Meaning or semantic components hint at the meaning of the character, e.g. the 女 (woman) component in 妈 (mother) seen above.

Meaning components are color-coded as red. - Sound or phonetic components hint at the sound of the character, e.g. the 马 (mǎ) component in 妈 (mā) seen above.

Sound components are color-coded as blue. - Iconic components are direct visual representations of an object or idea. Traditionally, these are called pictographs and ideographs, where pictographs are pictures of objects, such as 木 (tree) or 山 (mountain), and ideographs are representations of abstract concepts, such as 三 (three) or 下 (down). In practice, I often found the distinction between pictographs and ideographs to be subjective and not so important. For example, is 大 (big) a pictograph or an ideograph? For this reason I classify both types of characters as “icons”.

Iconic components are color-coded as green. - Unknown components are components that I’m not sure about. Unfortunately, not all Chinese characters have a clear explanation.

Unknown components are color-coded as gray. - Simplified components have been changed from their traditional form in character simplification to reduce the number of strokes.

Simplified components are color-coded as teal. - Deleted components exist in the traditional form of a character, but were deleted for simplification.

Shortcomings

I’ve done my best to try to be as accurate as I can, but I’m sure there are errors in some of my explanations. I’ve learned a lot during the process of researching the origins of over a thousand characters, but I don’t claim to be an expert in the history of Chinese writing.

On top of that, many characters have an unclear history, and nobody really knows exactly how they came about. Sometimes I just chose an explanation that seemed plausible and made sense to me, and other times I just gave up on trying to figure it out and wrote “Origin unclear”.

Occasionally, I have decided to oversimplify the explanation and omit details that will not be helpful to people learning Chinese. Some characters have a long and convoluted history that would take pages to explain fully. Since my intended audience is people learning to read Chinese, rather than academics researching Chinese characters, a brief white lie can be preferable to the real explanation with lots of arcane details.

In any case, if you see a mistake or want to suggest an improvement, you can help out by opening an issue on my Chinese lexicon repository.

Sources

The most reliable and comprehensive source for character origins available online that I’ve found is the 漢語多功能字庫 Multi-function Chinese Character Database provided by The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

I’ve also found Wiktionary to often be useful, although the explanations there are often missing or inaccurate.

The 說文解字 Shuowen Jiezi is an ancient dictionary that is a remarkable work of scholarship for its time, and for thousands of years was treated as the bible for character origins, but in the last century, research into Oracle bone script has revealed that many of the explanations in the Shuowen are inaccurate.

The Chinese etymology website by Richard Sears is the best source I’ve found for finding images of historical forms of Chinese characters.

Want to learn how to read and write Chinese? Sign up at Dong Chinese.